|

. |

|||

|

AMERICAN CINEMA PAPERS

2015

VENICE

2015 – LIONS AT MIDNIGHT

|

VENICE

2015 – NO STRINGS ATTACHED

PUPPETS OF LOVE by

Harlan Kennedy

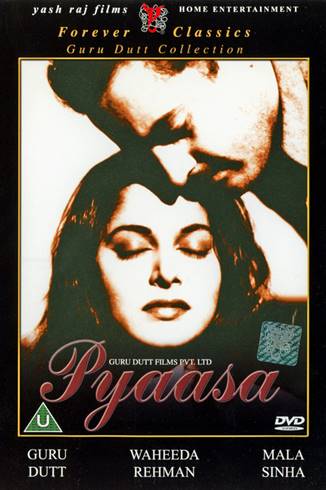

“Love’s puppetry is the theme of the great Indian film PYAASA. You need no marionettes, just the tragic passions of the human heart in an inhuman world, to create a mortal ‘puppet’ drama as poignant as any on folk art’s tiny stage.” Rabindranath Bindhi, ‘Cinema’s Other Worlds’ “Due to the painstaking process of stop-motion animation, we were afforded the opportunity to explore the small, intimate and mundane with a uniquely precise attention to detail. Each fraction of each second was conceived, choreographed, performed and photographed separately. A film that might have been shot in two weeks with live actors was shot with puppets in two years. Through this arduous, intense collaboration with our voice actors, animators, artists and technicians we were able to live fully inside each character in every moment of the story.” Charlie Kaufman and Duke Johnson, co-directors of ANOMALISA. Love has its own language. So do the names of two standout movies shown at the 72nd Venice Film Festival. ANOMALISA and PYAASA. Strani titoli! (Strange titles!) In what exotic, or erotic, tongue do these two films, wonderstruck meditations each on romance, change and epiphany, announce themselves? Are they the names of characters? Of places? Of maladies? Of melodies? You may not find out till after you see each film. Or you may find out as you venture to the end of this piece. Either way, never mind the labels, feel the lyrical contents. As the alpha and omega of a festival rich in the strange and haunting – one film shown early, the other late – they were as twinned in theme and mood as they were, and are, sundered in time and distance. One comes from modern America, the other from mid-last-century India. One is in colour with a novelty style and bravura technique. The other is in a 1950s black-and-white, newly cleansed by restorers after half a century’s blips and blemishes. Both films are about love: its charm and spell. Also its merciless, marionetting power. That power is tackled poetically and figuratively by PYAASA, in the shadow-play enchantments of its eastern imagination. It’s tackled literally by ANOMALISA. The sombre seriocomedy of this film’s romance – a life-changing one-nighter in a Cincinatti hotel – takes the shape of a stop-motion puppet drama. A serious puppet drama? It could only come from Charlie Kaufman, antic imaginer of BEING JOHN MALKOVICH and THE ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND. He wrote the film and co-directed it with stop-motion animator Duke Johnson. Honoured on awards night at Venice by the Grand Jury Prize, ANOMALISA is an inspired combustion caused by the meeting of contrasting components. Sad-farce humanity meets toytown formalism. A British customer services guru and self-help author, uptight, travel-weary, his puppet self voiced by the chippy burr of actor David Thewlis, deplanes in a US town for a night’s rest and recreation in a business hotel. He’s skedded to give a speech on the morrow. Whiling away the evening in the hotel’s cocktail lounge – a singles bar in all but name – ‘Michael Stone’ (Thewlis) ends up with a date, even a choice of dates. The women in ANOMALISA are puppets too, of course. Pretty ones, even though all but eventual conquest Lisa, voiced by Jennifer Jason Leigh, speak with male voices. One male voice actually: that of actor Tom Noonan. He’s a survivor from Kaufman’s experimental stage and radio play, the origin of this film, where Noonan multitasked as all the supporting characters. Something is weird, and getting weirder, about this one-night wonderland in Ohio….. We’ll be back. Meanwhile in India, in 1957, the screen is sparkling with joy and music. Actor-filmmaker Guru Dutt’s sexagenarian classic was the sexiest film in Venice. Just like ANOMALISA it introduces love’s young dream – after an opening scene whose ‘clouds’ of unknowing and anticipation are those of the poet hero’s mind rather than the fleecy floor of an intercontinental plane journey – and shows it turning to nightmare. In India’s Bollywood, though, they sing even in adversity. Hero-hearthrob Vijay is played by Dutt himself: think of Johnny Depp crossed with Robert Donat (unless you’re too young) and add a ton of eye shadow. The verses of this wannabe bard are mocked by his brothers but loved by the upscale hooker to whom love and destiny are about to hook him. His poems and ditties make good production numbers too; almost everyone, even the film’s tortured souls, sings them. Show-stoppers include “When I asked for flowers I was given a garland of thorns” (I’m thinking of adding this to my repertoire) and, for a big-resonance climactic ensemble, “Who is there who claims to proud of India?” Vijay, like ANOMALISA’s Michael Stone, is a wandering soul looking for love and fulfilment. Given the heave-ho by his millionaire publisher, he falls into despair and drink. But even in life’s gutter he looks to the stars. And he’s still looking when pushed into a mental asylum. Here his spiritual crisis is taken for madness, though he still dreams, invincibly, of return and recognition. Meanwhile the world has discovered his genius. Sales of his slim volumes are skyrocketing. Only snag and irony: the planet thinks he’s dead. None but the lovely hooker knows otherwise, for reasons we can’t stop to explain or we’ll be here for 1,001 nights. Can the two re-meet? Will love happen for him/her? Will reward and acclaim embrace him in this world? Or will he reach the next world first?.... ANOMALISA, meet PYAASA. PYAASA, meet ANOMALISA. The difference between the two films captures their eerie kinship. Each is a pageant of fate’s puppeteering power, of men and women as marionettes of love, fate and twisty destiny. Yet treading the same terrain, the two tales travel in opposite directions. Each is carried on a differently spellbinding arc by its different epoch, country and tradition. PYAASA begins as a story individualised and idiosyncratised: a misfit hero being pinballed around a misunderstanding society. Then it leaves the local and parochial for the tragical-romantic and the Bollywood-inspirational. Much as the actual production did (records attest), starting in Calcutta locations before the Bombay soundstages. The hero and hooker heroine become ‘puppetised’ poetically in the move to romantic enlargement. They are made archetypal, talismanic, numinous. The world of Bollywood opera-drama tunes its tuttis for the climactic moment when we realise it might truly be the next life not this that delivers on men’s dreams for happiness and love. ANOMALISA goes the other way. It starts impersonal and generic. Looking at the almost literally ‘wooden’ characters in early scenes, we contemplate an endurance test of talking toys treadmilling the tropes of an allegory-romcom. (In actuality, while they look like wood, the puppets were created by 3D printers. A first for feature-length model animation). But individualism and quirkiness creep into the story like a redemptive virus. Tenderness transfigures the transient. As the hero finds love, so the audience discovers humanity: that of the story and of the characters. (Not that the comedy stops. There’s a puppet sex scene to match the graphic, Dadaist incongruities of TEAM AMERICA). Michael and Lisa, our chance dates in jet-age stopover land, no longer seem puppets at all. The delicacy of the film’s surrealism and the spell of its grave-but-droll dialogue prepare us for this. By final scenes the souls have sloughed the surly bonds of whittled teak; or whatever substance makes puppets in 3D printers. Michael goes on to give the speech of his life the next day: the Demosthenes of customer service and human communication. In the same way – though by a different narrative and artistic trajectory – Vijay gets the oration of his life to wind up PYAASA. Moral; if you survive the worst and best that existence can throw at you, you get to lecture the rest of us, still struggling with those perfidious impostors called Life and Love. By the way: those titles. PYAASA is Hindi for ‘thirsty’. The theme, you could say –exalting ‘thirst’ to its higher and more metaphorical meanings – of Guru Dutt’s whole movie. ANOMALISA isn’t Hindi, or English, for anything. It’s a verbal flight of fancy formed from ‘anomaly’ and ’Lisa’; though we can surely add the observation that it’s also a near-anagram of ‘Mona Lisa’: that enigmatic portrait sitter, the humanity of whose half-smile seems to reach beyond – so far beyond – the artist’s puppet stage of wood, paint and canvas. Yeah, that’s it. COURTESY T.P. MOVIE NEWS. WITH

THANKS TO THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD

CINEMA. ©HARLAN

KENNEDY. All rights reserved |

|

|

|

|

|

||

![P2-ANOMALISA POSTER images[1]](VENICE_2015_PUPPETS_OF_LOVE_files/image007.jpg)