|

. |

|||

|

AMERICAN CINEMA PAPERS

2010

|

VENICE 2010 – THE 67 th MOSTRA

DEL CINEMA THE WIND AND THE LION by

Harlan Kennedy

Winds howling across the

lagoon. Lion statues tumbling down steps. Festival officials tossed about

like balloons. (Isn’t that Marco Mueller himself, Mostra

del Cinema chief, flying over a roof?) Rain descending like giant combs to

sleek and slick the hair of hurricane-lashed trees. We knew the 2010 Venice

Film Festival would close with a

tempest. Julie Taymor’s film of Shakespeare’s play,

starring Helen Mirren as a female Prospero, was the scheduled last-night

gala. We didn’t know a tempest would begin the event. But how great to be on

an Adriatic island when hell breaks loose. Action, spectacle, elemental

music. You think you have died and gone to a Cecil B DeMille

movie, laid on as a billion-dollar film

sorpresa at the Mostra

del Paradiso. This was the year

Mueller said everything would be different. For a start there were three

opening films, not one. On the first night the Palazzo Grande audience –

nobs, toffs and designer-dressed signorinas – sat

white-knuckled through a trio of thrillers: Darren Aronofsky’s

BLACK SWAN (blood at the ballet), Andrew Lau’s LEGEND OF THE FIST (punch-ups

in Peking) and Robert Rodriguez and Ethan Maniquis’s

MACHETE (gore galore, siphoned off from RR’s spoof trailer from GRINDHOUSE).

The evening of harum-scarum entertainment was planned to illustrate Mueller’s

newest pronouncement on movies: something about a “contract between the

filmmaker and his audience,” ignoring or combining genre differences, from

which the audience emerges shaken and stirred while the filmmaker, like a

barista making a good cocktail, takes the compliments and the money. Ah Venice. It’s always

different. Not just from year to year but from day to day. The clouds had

barely drawn back on the morrow to reveal the usual blue skies when we were

in art business as usual. Three pics from around the globe qualified as best in fest.

They came, in order of projection, from Japan, Russia and China. They each –

you could say if you were looking for a tema della mostra (theme

of the festival) – explored the potential drama and communicability of inner

states or esoteric ambiences. Not excepting, indeed

distinctly highlighting, the realm of death. NORWEGIAN WOOD. Tran Anh Hung from Vietnam, a former Venice Golden Lion winner

(CYCLO), is the helmer entrusted with Japanese

novelist Haruki Murakami’s international

bestseller. It’s been read in 30 languages. It’s got a Beatles song for a

title. (We’re in the 1960s). Yet its tale of suicide, depression and wayward

love, clumsily handled, could have sent world audiences screaming to the exit

doors. Watanabe, the hero-narrator, loves two women, the depressive Naoko and

the life-loving Midori. He tries to juggle the romantic tasks but finds them,

if anything, juggling him, The novel was full of

antic, anguished mood changes elegised by recall. Tran, directing, finds a

screen style to suit. Images of nature – mainly the grasslands and mountainscapes around Naoko’s mental convalescence

retreat – have an animistic power (wind, rain, changing colours, fluctuating

textures) while the humans seem transfixed each by his own, or her own,

comedy or tragedy. Hypnotic at its best, the film has a starmaking

performance from model-turned-actress Kiko Mizuhara, whose Midori, combing

the wilful and wistful, is Murakami’s character to the life. OSVYANKI

(SILENT SOULS). Russian cinema is unbeatable for tales of epiphany at the edge of the

world. See its last Golden Lion winner, Andrei Zvyagintsev’s

THE RETURN. Alexei Fedorchenko’s film unfolds in a Finno-Russian remoteness, where the old ways cling on

surreally, decayingly, like the snaky pontoon

bridges, crumbling factories, desolate highways. This is the land of

torch-lit midnight atavism. The land of what seems to us a social-historical

trance state. Are we really in a community, the ‘Merjans’,

where a widowered spouse, such as the factory boss

friend of the hero (a paper-mill worker and amateur

cartographer/ethnographer), whose wife has died, takes his deceased partner

to a beach and burns her on a pyre? Before that he and the hero hand-wash the

woman’s body and tie ribbons to her pubic hair. It’s a tribal tradition. The

surviving mate also reminisces aloud – it’s called ‘smoking’ – about his

bygone sex life. “All three of her holes were working and I unsealed them.”

Crikey. This is Russia? Politically

and socially repressed for the last 100 years? The film is spellbinding, like

a wound reopened so the air can reach it and friendly animals can lick it.

Bereavement, and Russia, with a human dimension. THE DITCH. Now we go to

China. Wang Bin’s movie, sprung on us as this year’s film sorpresa, is a gruelling account

of a re-education camp in the Gobi Desert. Time: 1960. They weren’t listening

to Beatles’ songs back then. If they had been, it would be ‘A Hard Day’s

Night.’ That’s what life was. Hard labour under a searing sun, shivering

sleep (or more labour) under a cold moon. The men bunked – according to this

film based on documents and survivors’ accounts – in rat-infested dugouts,

hence the title. People became corpses and were carried out, trussed in their

last blanket. Food was rat soup, seeds scrabbled from the desert or sometimes

– look away now – the best-looking bits from your friend’s vomit. Wang Bin

can’t quite sustain the cold horror. A midsection with a bereaved wife

seeking a vanished (and, we learn, cannibalised) husband seems routine: just

tears, wailing, agony, despair. The real unbearability of this story is the way the doomed men

just get on with it. Eating the uneatable; remembering things too painful to

remember (like freedom); watching their own souls, minds and bodies shuffle

forward in the queue for death. A new Russia? A new

China? Countries which can produce films like these, candid, countercultural,

counter-revolutionary? Human? Holistic? Which is to say,

complete in the understanding of the holes humans dig for themselves – and

must then find ways to transcend or escape. The Venice Film Festival

had its own hole. Its own ‘ditch.’ Its own quarried habitation for the

sighing of silent souls. I mean the building site where the new festival

palace is going up. Or would be if the project weren’t going over-schedule.

The latest delay to a building planned for inauguration next year is the

discovery of an asbestos burial site. Yes, it’s a toxic

Mycenae. Festivalgoers skirt the bio-hazard, as large as a necropolis, and

marvel as they circumambulate at the traces of pink

and pillared ruin on the excavated sides. Great gods and little caryatids,

were temples once here? Or sacrificial shrines? Or an ancient forum?

Everywhere you go in Italy, or everywhere you dig, seems to turn into history

and romance. FELLINI ROMA Part 2, Part 3, Part 4…. Dangerous too. This

year, if you opened the wrong door to flee a bad movie – and there were a few

– you could fall straight into the giant hole. Down you plunged, to where

asbestos-formed monsters, retired festival directors, or old corpses of

Venetian doges, embraced you slitheringly or tried

to drag you deeper down, perhaps to hell itself, which in this abyss is one

floor down after ancient kitchenware, lost digging tools and broken Roman

pottery. Fear not. These were

only dreams or nightmares. Fest boss Mueller, dressed in black, went about

reassuring us the hole would be a

palace one day. La Cenerentola (Cinders) will go to the ball. Meanwhile happy

times were available this year watching, for instance, that wild notion of

Marco’s for an opening triple bill: the noblest men and women, in their

finery, splashed with blood from seven to midnight. Marco has only one year

left of his second four-year contract. Was this a farewell Walpurgisnacht? Or a phantom-of-the-palazzo gig from

a man who dreams of staying on as a spirit to dash about the Lido kinos and haunt their rafters, in future Mostras, now and then dropping a memory like a giant

chandelier? Marco has a good record:

let it be taken into account. And though the 2010 Venice festival was not his

finest, count the number of talking-point movies. The prattling classes had a

lot to say about Abdellatif Kechiche’s

VENUS NOIRE, for instance, closely followed by Jerzy Skolimowski’s

ESSENTIAL KILLING and Pablo Larrain’s POST MORTEM. VENUS NOIRE re-enacts

the true history of the Hottentot Venus, the African woman whose stupendous

attributes – including prominent posterior and protrusive pudenda – became

the craze of Europe in the early 19th century. She was a circus

star, salon celebrity and curio for anthropologists. Finally, when luck

waned, or so claims writer-director Kechiche (whose

last movie was another provocateur tale of ethnic collision, COUSCOUS), she

was a sex worker satisfying men who liked it racially mixed. At 2 hours 40 minutes,

little is left unsaid about race and gender attitudes two centuries ago –

about prejudice and prurience – and much of it is said fortissimo Andre Jacob and Olivier Gourmet, playing the

consecutive masters of ‘Venus’ (real name Saartjie Baartman), shout their dialogue to the rooftops. Down in

the bearpits of what passed for society, in London

and Paris, the baying toffs prod and paw the poor girl – to the point where

Venice audiences said Kechiche was exploiting his

actress, Yahima Torres, in the same way the world

of 1810 exploited Saartje. You pays

your Euro and you forms your verdict. Me? I thought the film’s fault was not

its complicity in the voyeurism it purports to condemn, but rather the

lecturing, hectoring tone. At shorter, more teasing length it could have genuinely allowed the filmgoer to

think for himself, instead of suspecting he was being mugged by an

ideological highwayman saying, “Your agreement or your life.” ESSENTIAL KILLING is a

skilful manhunt flick about an escaped Afghan jihadist (Vincent Gallo),

pounding the Polish snows as he flees men depicted as CIA torture-transit

goons. Skolimowski evidently went nutty in the

editing room: the 83-minute story contains lacunae and non-sequiturs. (How did the protagonist replace his torn

and ratty prisoner threads with that handsome, perfectly fitting white

jumpsuit he suddenly wears in a new scene?) But at least we are posed an

interesting question. Can an adventure story, confidently told, get us

rooting for the last person on earth with whom we’d normally identify? POST MORTEM is about

sex, autopsy and the corpse of Salvador Allende. Chilean director Pablo Larrain made the morbidly brilliant TONY MANERO, a

SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER riff whose protagonist had a white suit and diseased

mind. Actor Alfredo Castro – mouldering pallor, shoulder-length hair –

returns as a mortuary scribe, taking down autopsy details until the day the

assassinated President appears before him on a slab. Place: Santiago. Year:

1973. What effect will this sudden drafting into political history have on

the hero’s creepy love life? His ex-stripper girlfriend, caught up with

dissidents, is hiding behind a wall in his house. How long will she stay

there….? Yes, creepy is the word. Larrain has

cornered a part of the movie market where the meat starts to stink a little.

For low prices – his films look as if they cost almost nothing – he will sell

you something with the unforgettable odour of mortality, and sometimes as

here, a spice of wit, even wisdom. The weakest films at

Venice went to the wall, in quite a different sense – or perhaps not – from

the heroine of POST MORTEM. Personally, I would like to wall up alive Sofia Coppola’s SOMEWHERE. Or to bonfire as a vanity

this LA-set variant on SC’s LOST IN TRANSLATION. Where Scarlett Johansson and

Bill Murray marooned in a Japanese hotel were magic, Stephen Dorff as a spoiled film star and Elle Fanning as his

estranged teen-brat daughter stuck at the Chateau Marmont

are not. Too much like Lalaland realism: the truth

at 24 narcissistic whinges a second. Julian Schnabel’s MIRAL

is one man’s UN-style statement about how Israel and Palestine should live

together in an ideal world. Unfortunately Shnabel’s

ideal world appears to consist of bimbo casting (the vapidly decorative Yasmine al Massri as the

orphan-of-discord heroine), bumper-sticker dialogue and the kind of flatulent

liberal generalities that gave Stanley Kramer’s cinema a bad name. Better, if not by a

mile, was Tom Tykwer’s THREE, an infidelity

drama-comedy that breezes along until we realise the man and woman two-timing

each other are doing it with the same guy. German cinema is crazy for this

kind of polysexual screwball romp. She gets

horny-hetero, he gets horny-gay and the cynosure of their desire is a

baby-faced stem-cell scientist who looks like a Botoxed

Gordon Ramsay. Weird. There’s a biological-philosophical idea – none too

convincing – that human sexuality is really a blank cheque (like a stem-cell)

that gets filled in by volition not destiny. Hmmm. As a partner-swapping

romp, it was at least better than Anthony Cordier’s

HAPPY FEW, a swingers’ rondo from France and by pretty general consent the

worst movie in concorso. Never mind! Whenever we thought all

was lost at the 67th Venice Film Festival, winners blew in like

tumbleweed. They might be slender, might be modest, but they indicated life

and growth in the desert. Among small pleasures my favourites included

Patrick Keiller’s ROBINSON IN RUINS and Kelly Reichardt’s MEEK’S CUTOFF. The first is a British

pastoral documentary – how else describe it? – from

a filmmaker whose past works (LONDON, ROBINSON IN SPACE) teasingly trace

social/cultural/economic history in the curves and tilth

of the UK countryside. Sometimes Keiller is drily

authoritative, at others a seriocomical tease.

‘Robinson’ is his unseen protagonist, a German-born agro-boffin supposedly

cast away on the Britannic isle (like Robinson Crusoe) to sleuth the

footprints of a nation’s past, present and potential future. Kelly Reichardt, in MEEK’S CUTOFF, bounces back from that damn

film about a dog everyone liked and I didn’t, WENDY AND LUCY. This is an

eschatological western, exploring the point where hope ends and so might life

as a three-family wagon train gets lost in the Oregon desert. They end up

trusting to a dodgy white guide (Bruce Greenwood) and dodgier Indian captive

(Rod Rondeaux). In bleak and fabulous landscapes

the skeletons of despair start to show, as if x-rayed, through the Quaker

clothes and the youthful trusting faces. Reichardt, despite

seeming to expand into genre cinema with a big-landscape movie about settlers

versus Indians, takes care to tell us she’s still an indie director at heart.

There are few concessions to spectacle. The screen is box-shaped, literally

square as if shot with a primitive, pioneer camera. The cast is sub-stellar,

though led by Michelle Williams. So it was left to Ben

Affleck’s THE TOWN and Richard J Lewis’s BARNEY’S VERSION to represent ‘Hollywood’

in the Mostra main event. Affleck’s Boston-set bank heist thriller scores for pace, script and idiomatic

characterisation. This actor-turned-director, synonymous with career suicide

back in the GIGLI/PEARL HARBOR days, keeps getting his professional

credibility back in Venice. Four years ago he won Best Actor here for

HOLLYWOODLAND. Did it help that he had brother Casey in Venice this year – a

recent near-miss himself for Best Actor when he was pipped

by co-star Brad Pitt in THE ASSASSINATION OF JESSE JAMES. Casey was squiring

his likable, funky doc about Joaquin Phoenix, I’M STILL HERE. BARNEY’S VERSION crashes

through the usual stations of sentimental agony associated with a Mordecai

Richler novel. Main point of interest: star Paul Giamatti.

Playing Jewish he seems spookily like a new-millennnium

reincarnation of Richard Dreyfuss: manic, emoting,

eye-rolling, a ‘lovable’ grown-up baby at war with everything adult. The

whole film tries a bit too hard to be loved. The coolest thing on show is the

best: Waspy British actress Rosamund Pike (late of

AN EDUCATION), glacial and gorgeous even though weirdly cast as a Jewish wife

and mama. Stars? There weren’t too

many tripping the red carpet this year. Probably too risky for the big-name

celebs. They might take a wrong turn and fall straight into the building-site

hole. But nothing keeps Catherine Deneuve or Gerard

Depardieu away from the spotlight. They were the stars of Francois Ozon’s POTICHE, the purest, silliest fun of the festival.

It’s an adapted stage comedy, a boulevard trifle

about a factory boss (Fabrice Luchini)

forced to retire by his ambitious wife (Deneuve) in

collusion with the ex-communist mayor (Depardieu). Luchini

then becomes the ‘trophy husband’ of the title. Ozon

directs with all campy barrels firing. Deneuve gets

to sing. Depardieu is barely restrained from dancing. Fun is had by all, not

least the audience. A feeling of ‘seize the

day,’ or as they said in these parts 2,000 years ago, ‘carpe diem,’ was

hardly surprising. On the Lido this year reminders of change and finitude

were everywhere. Not just that hole in the ground, but the apocalyptic news

that the Hotel Des Bains will close to become a set

of luxury apartments. It will preserve a small part for wealthy overnighters.

The rest will become Condoland on the Adriatic. Hotel Des Bains? Doesn’t ring a bell with

you? Oh reader, hear the bells that rang long ago from room to kitchen, to

front desk, to bar service, to tuxedo-pressing. Thomas Mann, Gustav von Aschenbach, Dirk Bogarde and Luchino Visconti all stayed there, respectively the

author, hero and screen star and director of DEATH IN VENICE. Everyone once stayed here. I once stayed here.

The place was a bella epoca legend. Closure too, though

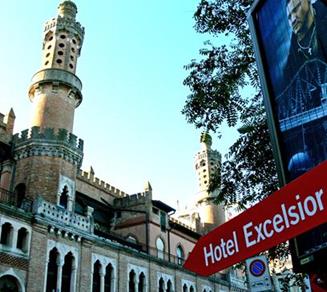

temporary, is the sentence passed for next year on the Excelsior Hotel, the Lido’s other palace for the plutocracy. It will

close for improvements. Look at the place, dear reader. Does it look as if it could be improved? But we mustn’t stay the

hand of history. All will be better in the best of all possible festival

islands. And by 2011 we will have swapped a cuckoo jury for a sane one. This

year’s delivered the most gaga prizes on record. The Golden Lion went to

Sofia Coppola’s SOMEWHERE – I haven’t changed my opinion, see paragraph 20 –

while the runner-up Special Jury Prize was handed to Skolimowski’s

ESSENTIAL KILLING (see paragraph 18), for which Vincent Gallo won Best Actor.

Best Actress went to Ariane Labed,

playing the alienated daughter of a dying architect in Athina

Rachel Tsangari’s Athens-set ATTENBERG, which is,

in essence, SOMEWHERE done as whimsical Greek tragedy. With howling injustice

China’s THE DITCH and Japan’s NORWEGIAN WOOD went prizeless,

while Russia’s SILENT SOULS was fobbed off with Best Cinematography. (Nice

hands, dear). Yes, we definitely need

a better jury or jury president. Get me Henry Fonda. Or alternatively get me

last year’s jurors, who not only nailed the Best Film – LEBANON – but got

every other prize right. As befits a team led by Quentin Tarantino, this

year’s jurors were inglourious basterds.

Another Adriatic hurricane such as the one on the first day will deal with a

similar jury if picked again. In the meantime, book my

gondola for 2011. It is the 150th anniversary of Italian

unification. It will be the party to end all parties. Viva L’Italia. Viva Garibaldi. Viva la Mostra. COURTESY T.P. MOVIE

NEWS. WITH THANKS TO THE AMERICAN

FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD CINEMA. ©HARLAN KENNEDY. All rights reserved |

|

|

|

|

|

||

![Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: Description: E:\HK\HK OFFICIAL PICTURE - LARGE & SMALL\HK[1].jpeg](VENICE_2010_files/image019.jpg)