|

AMERICAN CINEMA PAPERS

2004

|

THE

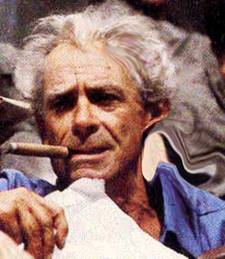

BIG RED ONE MOVIE LEGEND SAM FULLER SHOWS AND TELLS – IN CANNES AND PARIS by Harlan Kennedy He fought in wars. He stormed beaches. He

battled Hollywood moguls. He was an old dogface and proud of it. Sam Fuller

looked as if he’d lived through a thousand explosions – some of them coming

from inside him – and his smoke-white hair, blazing eyes and fissured face,

tough as a walnut, were the testimony. The Cannes Film Festival, the ‘Big Azure

One’, is the battle front of world cinema and Sam was always proud to be

there. He loved to pitch in among peers, to talk pictures; to paint pictures for you with his

stories and memories. “Oh y-e-a-h!”,

he’d say, grabbing your sleeve and burning a hole in your eyes with his own.

And he’d be off into tales of love, death, war, moviemaking. There were friends by the hundreds for him at

Cannes. Film lovers, comrades in arms, the French in general. He lived in Paris

in his last years, maybe for gratitude. The French knew him for a genius

before anyone else. They gave his films the run of the Cinematheque. They

wrote essays on him. No sapient person in the country that invented

cinemagoing would give you a blank look

if you spat out

Sam’s titles like a repeating gun. STEEL

HELMET, MERRILL’S MARAUDERS,

UNDERWORLD USA, HELL AND HIGH WATER, PICKUP ON SOUTH STREET. Jean-Luc Godard

even cast him in a film. Sam played himself in PIERROT LE FOU. Featured in a

party scene, he rasps out the most famous line in all Godard’s cinema. What

is film?, someone asks. “The film is like a battleground. Love, hate, action,

violence, death. In one word, emotion.” He said “emotion” like he meant it. “E-moh-shun!” (Like “Ex-ploh-shun”). Today in ways Fuller couldn’t have predicted, as the

entire planet gets digital, emotion seems more than ever the perfect word for

the art of the moving image. After e-mail and e-ticketing – ‘e-motion’.

Motion electronically charged and conjured, on a zillion TVs by a zillion

computers and DVD players. The French gave their favourite adopted

filmmaker one last glorious send-off at Cannes this year. Fuller would have

loved to have been there himself, but couldn’t be. He had fallen finally in

1997 – that last fall, death – aged

86. But his battle epic THE BIG RED ONE, a World War 2 movie that begins in

World War 1, was there to represent him. The film had been royally

reconstituted, in what you’d call a director’s cut if the director had been

around to cut it. Instead US critic Richard Shickel

had done the snip-and-add stuff, and the Salle Bunuel in the Cannes

Festival Palace was where several hundred gathered to cheer the great

dogface’s last bigtime film testament. Sergeant Lee Marvin and his four grunts,

hauling themselves from North Africa to Sicily to Normandy to Berlin, now

have a little more screen time to live it like it was. The journey of combat,

murder and death, those stations of the Cross that human beings live out

every time the world goes to war. (Is it coincidence – surely not – that the

movie begins and climaxes with that mysterious Cross in the wasteland?) In a preface to his novel of THE BIG RED ONE

Fuller, who served in the eponymous infantry division in World War 2, told us

what he intended with book and film. “This is fictional life based on factual

death. Any similarity the names have to any person living, wounded, missing,

hospitalized, insane or dead is coincidental.” That’s telling ‘em. And Fuller told us something else, something

mischievously seditious, in the very way he made the picture and the location

he chose. The Sahara, Sicily and

Northern Europe were all played by – Israel! Jews took the roles of Nazi

soldiers, wearing German helmets over yarmulkas.

The concentration camp at Falkenau, Czechoslovakia,

was filmed in the heart of Jerusalem. Jewish death camp survivors played the

People’s Army fighting for Hitler. Is that why THE BIG RED ONE seems more like

some surrealist pageant, some vast and antic comic-book apocalypse, than a

regular war flick? Or like some momentous mystery play drawing its audience

after it as it travels from despair to hope, cynicism to salvation, horror to

faith – not in God but in a brave, defiant survival instinct that will see

humanity through, to the next trial of fire, then the next, then the

next. In its new version the film is almost

everything Fuller fans wanted, though maybe we still hanker for the ideal war

movie proposed by Sam himself in the afterword to

that novel version of THE BIG RED ONE. “To make a real war movie would be to

occasionally fire at the audience from behind the screen during a battle

scene. But word-of-mouth from casualties wouldn’t help the film to sell

tickets. And again, such reaching for reality is against the law. Anyone

seeing the movie or reading the book will survive.” I met

Sam Fuller once at the Cannes Film Festival and later again in Paris – long

years ago, when THE BIG RED ONE was a gleam in his eye, or maybe a gleam at

the end of one of his torpedo-like cigars. (He was like Conrad’s narrator

Marlowe, conjuring tales of death and horror from the genie glow of his

cheroot). In Fuller’s small walk-up apartment in a seen-better-decades

building in the Rue de Reuilly in south-eastern

Paris – an artist’s garret in all but name, where Sam barely had room to

swing a Havana but could always light out to his favourite Chinese restaurant

nearby – we talked for two hours about everything and anything. I can’t pretend to duplicate on paper his

sound and manner in full flow. You half-know it already – from his cameo

roles for Wim Wenders in

THE STATE OF THINGS and THE AMERICAN FRIEND – but the reality outstrips the

screen replica. Fuller rasps, barks, singsongs, whispers, hisses, confides.

He’ll deepen his voice for a gravel-growled basso profundo

to speak of some unforgotten betrayal or act of bad faith. Then he’ll go

near-falsetto with excitement – “Yi-yi-yi-yi!” –

when speaking of an actor, director or movie he loves. The ultimate Fuller signature sound, though,

is the hiss of passion to climax a speech, a cresting wave of exclamatory

ratification, breaking on the beach of an anecdote, memory or statement of

faith. “Oh y-e-a-h!” Or “Ahhhhhhh!!” or “Whaaaahhhhh!!!” It is often accompanied by a frenzied

grasp of the listener’s sleeve and the transfixing of him with a glittering

eye like that of the Ancient Mariner reaching his story apogee. Playing my tape-recorded memories over, I

note that Fuller’s mind kept driving back to those five verities he had

summed up for Godard. Had summed up, in PIERROT LE

FOU, as quintessentialising cinema. Love. Hate. Action. Violence. Death. FULLER ON LOVE. (One day in the early

1950s Fuller had a meeting with 20th Century Fox studio boss

Darryl F Zanuck and FBI chief J.Edgar

Hoover, to discuss the “unpatriotic” elements in Fuller’s script for his new

movie PICKUP ON SOUTH STREET). “The

Richard Widmark character goes out and gets that

stolen microfilm from the Commies, that’s good,” Sam expounds, looking me in

the eye with an eye as bright as the cigar tip he is dangerously waving. “But

he did it for a girl ‘and that’s no

good!’ said Hoover. And Zanuck said, ‘But

that’s what we want! That’s a story! That’s true! That man I

believe in!’ This girl – it’s the first time anyone took an interest in Widmark’s character in the story. She even takes a

beating for him. There’s no love scene in my picture, Widmark

doesn’t ever say ‘I love you.’ He just says” – Fuller draws out each syllable

– “‘W-h-a-t’s the n-a-m-e of the m-a-n who beat u-p

on you?’ That’s all he wanted to know. ‘Who beat up on you?’ And Hoover hated that! ‘Cos

now it could have been any war, any flavour of victory or defeat. Politics,

who’s on whose side politically, doesn’t mean a thing when you’re a bum like Widmark and make a couple of bucks trying to steal a

watch and someone’s nice to you and you come to the hospital to see her all

beat up and you say, ‘Why did they beat up on you?’ ‘I didn’t tell them who you were’ – that’s all she says!” Pause

for wonderment. “Whaaahhhhh!!!

No music! I just had that camera move in. And she lies there. And he

looks at her. And that’s his love

scene!” FULLER ON HATE. “I got into trouble when I

made a film that brought out the racism in war. STEEL HELMET.” Fuller

takes a chomping puff on a new stogie. “Korean

war, independent 10-day picture, 104,000 bucks. I hadda

go to the Pentagon. All I wanted was some stock shots. I needed a shot of a

240-mm gun firing and hitting the side of a mountain. And they said” – slow,

deliberate, teeth-baring growl – “ ‘We

wouldn’t give you the sweat off our balls…Your picture is anti-American.

It’s unAmerican. It’s pro-commie. It’s everything

we loathe and that we’re fighting.’ Well, I did the picture, I went ahead and

did the picture – ‘cos this was a colonial

invasion! It was against the Constitution of the United States! One hunnerd percent! All these men in the Pentagon could’ve

gone to jail! Oh y-e-a-h!” – staring

Fuller eyes. “But we had a scene in the picture, very powerful, where the

Manchurian-Chinese prisoner of war, very intelligent, smart, who knew all

about the internment of Japanese nationals in America after Pearl Harbor, and that Chinese were interned too ‘cos nobody could tell the difference, turns to a Japanese-American

GI and says, ‘You have the same damn slant eyes as I. Then how come you fight

for these white sons of bitches

when you know they HATE OUR GUTS?” Fuller’s face blazes 12 inches from mine.

It’s as if I am the GI and the question is for me. After a minute’s

eye-locking he takes another cigar and moves on to another motherlode of memory, this time about the harum-scarum

logistics of location filming – or location filming Fuller-style. FULLER ON ACTION. “Robert Stack had his life

in jeopardy (making Fuller’s HOUSE OF

BAMBOO on location in Japan in 1955). I had three or four CinemaScope

cameras looking down into this shopping street where he’s supposed to run

after our only other actor – the rest of the crowd was real, they didn’t know

we were filming – says out loud ‘This white son of a bitch stole my watch!’

Well, Stack runs towards the camera and on the first take the crowd literally

ripped him naked!” Pause for effect. “I wasn’t allowed to use the

shot: Zanuck, when he saw it in Hollywood, was horrified.

Stack was very upset ‘cos that was a dangerous run.

They could have killed him, there were still high feelings in Japan ten years

after the war.” Later in the same movie an unrepentant Fuller

subjected Stack to real bomb explosions in an action sequence. “In America you can’t use nitroglycerine, TNT or dynamite. When I was told I could

use real explosives in Japan – oooohhhhhhhhhHHH!!!!!!!!!!!!!!.”

Look of deranged relish on Fuller’s face. “So we did use explosives. No

one was hurt – but I hadn’t told them I was using real dynamite, so when the

actors felt the ground shake and quake when they were filming you could see

the fear in their faces. You can still see it. That shot we used!!” All’s fair in love and film. When Fuller

breaks to fetch me some coffee, I feel that to keep the mood I should drink

it from a tin cup while shells burst around me. Death, the last adventure, is

always close in Fuller’s cinema. FULLER ON DEATH. “There is no law in war. But

we ‘make’ one,” he says with a derisive snap. “The Geneva Convention is

bullshit. Completely. A piece of

paper is nothing. What’s in your hand is a gun, and what’s in there is a

5-cent bullet. That’s your treaty, or no treaty. And when you see a man and

he gives up, you either shoot him or you don’t. You do it, you’re God!

There’s no president, no general, it’s the GI, it’s the Tommy Atkins, it’s how he

feels, right there. And if you’re on the wrong end of the gun and he

looks you in the eye, you know you’re gonna get it,

and you get it. One thing is” – sarcastic look – “you’re not supposed to

shoot a prisoner-of-war. I don’t believe in that! When a man came to us as a

prisoner-of-war, and he throws down his gun, his Mauser,

and puts his hands in the air, my sergeant would pick that Mauser up and he’d rack it back and if there’s a round in

there, just one bullet, that guy lives. But if he ran out of bullets, ohhhh” – look of caustic and cosmic

judgment – “we blow his head off. ‘Cos, isn’t that cute?? He shoots your friend here. He

wounds this guy. He wounds you. Kills that guy. And then he says to another

guy, ‘Don’t shoot!’ Why? Because he ran

out of amm-un-ition….!” He draws the phrase out like a

death-rattle, at once summation and damnation. There are many forms of violence and Fuller

has depicted most of them on screen.

But he pays homage too to the other artists who have excelled at portraying

other cruelties and emotional violations.

FULLER ON VIOLENCE. “Noel Coward. Phenomenal!

Man of the theatre. Great!! Not just good but great. He made people laugh.

But he loved movies too. He acted in them, wrote them, directed them. BRIEF

ENCOUNTER! Yi-yi-yiy!” The voice does a jig of admiration.

“For me the greatest story of violence in the world is not physical, not

Wayne walking into a bar and shooting guys or slugging them. But a married

man and married woman, not married to each other, are about to do something naugh-tee, and they’re embarrassed…!” He teases out the scene-painting with mock archness. “And the terrible emotional flavour of guilt –

each one afraid of even touching the other’s hand! – in that room. Trevor

Howard, Celia Johnson. And the fellow who’s lending the room comes in and

says, ‘Sorry, I forgot my key….’ And the moment breaks, and the horror of

that, and the fear, and the welling up of guilt, and the murder of their

passion – that’s true violence!” And for Fuller only movies can truly capture

it, as they capture truthfully so many things. We come to the conversation’s

last cigar and last hurrah. Fuller pays tribute to a ‘seventh art’ that is for so many the first

and foremost. In a late-afternoon

Paris apartment, the three most

brightly glowing lights are Fuller’s Havana and his two raptly envisioning

eyes. FULLER ON CINEMA. “In the arts cinema is

number one. Thousands of years from now,

they’ll be making movies. They’ll be showing them to more people on

more planets. It’ll be a universal language, in a way we have no conception

of today. “It’s the only art. If I want to show Lister in action, I’ll show closeups

of what he meant by that word ‘antiseptic’. If I want to show Goya in action, or Liszt

arguing about a certain musical note, I will see it, hear it, dramatise it. “It’s the only artform

in the world where all arts are on the screen. And it’s a weapon for peace. It’s the

greatest education for kids – the greatest – not to shoot or kill or hurt or

go to war.” COURTESY T.P.

MOVIE NEWS. WITH THANKS TO THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR CONTINUING

INTEREST IN WORLD FILM. ©HARLAN KENNEDY. All rights reserved. |

|