|

. |

|||

|

AMERICAN CINEMA PAPERS

2011

CANNES

2011 –

DANCING IN THE CLOUDS

CANNES

2011 – FICTIONS AND AFFLICTIONS

|

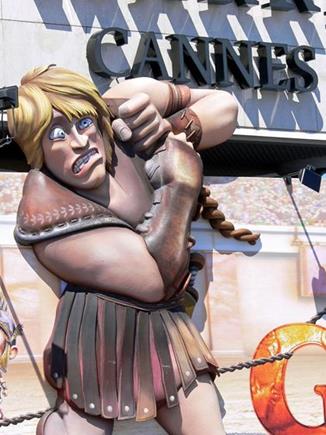

CANNES – 2011 THE 64TH INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL LIGHTING THE DARKNESS by Harlan Kennedy

What did we expect – what didn’t we expect – on arriving at the Cannes

Film Festival? The world’s greatest movie event is 64 this year: bonne anniversaire and many happy returns. What would we see as

we de-planed, debouched or de-taxi’d on the

Boulevard de la Croisette? Surely there would be a

Beatles tribute band singing, “Will you still need me? Will you still feed

me?” Fireworks would go off; a dove would break from the clouds; a giant hand

would reach down.,…. It wasn’t quite like that, but it was

pretty good. Cannes looked as gorgeous as ever, a Paradise on the Med, and

around the Palais steps on the first evening the

rubberneckers were setting up for a giddier-than-usual starspotting

orgy. Woody Allen, director of the opening night film, was there. Bernardo Bertolucci was official cutter of the opening ribbon. Jury

prezzer Robert De Niro

was accompanied by jurors Uma Thurman and Jude Law. And in ensuing evenings

the stars came down from the sky to take earthly shape – Brad Pitt, Angelina

Jolie, Sean Penn, Jodie Foster, Johnny Depp, Penelope Cruz ….Were there ever

so many screen celebs here in one year? We onlookers, wearing torn T-shirts

and holding hands to faces blanched with emotion, could only look up into the

night and howl, “Stell-ar! It’s stell-ar!” The main theme arrived instantly and

seldom went away. This was a festival whose films were obsessed with the

young. You never saw so many dramas crawled over by children or teenagers. It

was as if 2011 were a cue to replay like drowning persons our younger lives

or to prepare the planet for those who come after, assuming it survives. (The

Mayan calendar says the world will end in 2012. Lars von Trier says sooner). Terrence Malick’s

THE TREE OF LIFE, the big event for fans of America’s most gladdening or

maddening genius, was about kids growing up to learn about nature, grace and

revelation. There was a plethora of films about teens or pre-teens troubled

by the usual crises involved in leaving infancy. There were tots here,

urchins there, and the frightened little boy in Germany’s MICHAEL, a

paedophile abduction plot inspired by recent reality, up to and including the

lucky-break ending. Best of all, for me, was Luc and

Jean-Pierre Dardenne’s LE GAMIN AU VELO (THE KID ON

THE BIKE). The Belgian brothers have won the Golden Palm twice before, with

ROSETTA and L’ENFANT, so Cannes bookies scrawled “Not a chance” on

blackboards at the fest’s beginning. But the odds shortened overnight; the

night being that of GAMIN’s showing when the Palais

gave it a 12-minute ovation. They suspected, as did I, that this was

that rare and frightening phenomenon: a perfect film. The title kid is

brilliantly played by newcomer Thomas Doret: a combustive, breathless, full-alert energy, a face aged

with the precocious wisdom of victimhood. A motherless near-orphan trying to

break away from a juvenile home, 11-year-old Cyril stumbles – accidentally

and almost literally – into the arms of a young woman (Cecile de France), a

caring hairdresser, who agrees after a little coaxing to care for him. A storm of grief and rage erupts in the

boy when his elusive father (Dardennes regular Jeremie Renier), a thirtyish

wastrel, finally refuses to see him. The story skitters into a

crime-and-delinquency mid-plot, an +Oliver Twist+-ish episode with Cyril groomed for an assault/theft crime

by a smooth-talking artful dodger (his brief, ill-chosen father substitute).

But the drama regroups. One more grim surprise awaits.

But by now we believe in the grace and redemption forming, as if from the

very motes of street dust in the wake of the boy’s recurring bike trips. On his beloved velo – a modern-day mediaeval charger heraldically colour-matched

with Cyril’s clothes (black jeans, red shirt) – he is a knight of the winds.

The bike gives the film its rhythm, a perpetuum mobile

of hope and exhilaration edged with desperation. That makes all the more

effective the quiet, isolated moments when stillness descends on a scene and

when the Dardennes overlay, like a caress, a rare,

repeated musical gesture: a cadence from Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto. By the

film’s close nothing is finally resolved. But we have seen enough of the boy

– and seen enough into him – to recognize the possibility of salvation. Happy endings? Cannes was big on those.

Perhaps the mood was set by Woody Allen’s MIDNIGHT IN PARIS, the fest’s opener.

Okay, it’s a frivol. It could have been scribbled by

Allen 40 years ago, circa his famous time-traveller-meets-Madame-Bovary comic

prose sketch. Here Owen Wilson, incorporating deft Woody intonations, dips

back into Paree to meet Hemingway, Picasso, Gertrude

Stein and Co. It does the young hero the world of good. Bestowing a new

perspective, it enables him to ditch his tinny modern fiancée Rachel McAdams

and her snob parents. It also teaches him that ‘golden ages’ shouldn’t be

sought like sanctuaries in the past but worked for, with might and main, in

the present. Happy endings? Well, they weren’t

completely the rule. After the Woodywork the

festival hit a reef of doomy repetitiveness. Inside 24 hours we had three

films about troubled teens, all in English. The best was Julia Leigh’s

SLEEPING BEAUTY from Australia, a glacially curdled tale of sex and

prostitution, whose student with the Barbie doll looks (Emily Browning) is paid to take date-rape drugs so that elderly,

infirm or impotent gents can spend nights pawing her naked unconscious body.

(As in the well-known Aussie exhortation: “Throw another gimp on the

Barbie.”) Creepy? You bet. Nympholepsy

meets narcolepsy. In images so frigid and insouciant you could be watching a

series of Boucher tableaux adapted for Down Under. The two other tales of teen-related

trauma performed an odd dance of concealed cousinship. Lynne Ramsay’s WE NEED

TO TALK ABOUT KEVIN is based on Lionel Shriver’s novel about a demonically

dysfunctional kid and his strung-out mom. (Tilda Swinton does mom, or overdoes her, as a human scarecrow

in fright hairstyles). The film ends Columbine High-style with a school

massacre I found implausible, like most of this blending of autistic tragedy

with OMEN-style diabolism. Meanwhile Gus Van Sant –

whose ELEPHANT won the Golden Palm for its

powerfully persuasive picture of a high school murder spree – has sold his

mojo to Ron Howard’s Imagine Films. He presented the sappy, maudlin RESTLESS.

Two young funeral-crashers (Mia Wasikowa, Henry

Hopper) fall in love; she’s dying of cancer; he’s a heartthrob with a hidden

tragedy. It’s like BENNY AND JOON on tearjerk

drugs. Intrepid critics, faced with peril and pottiness at the one end of the Croisette,

do the sensible thing and make off to the other. Here are the homes of the

Directors Fortnight and Critics Week, main counter-event sideshows. The critic’s journey is taken at a brisk

walk, on legs that skilfully avoid the oncoming tsunamis of humanity: the tenue de soiree wearers advancing towards

the evening gala, the fun-seekers surging west towards the setting sun (scarletly matching the tapis rouge), even the Croisette buskers who

homeward plod their weary way after a day of Chaplin impersonation,

goat-balancing, breakdancing, firebreathing or

standing in goldpainted repose in the likeness of

Greek gods. What fun. And this year there was more

entertainment inside, once you reached Croisette

East. In the Directors Fortnight I loved Colombia’s PORFIRIO, directed by

Alejandro Landes. It’s the recreated true story of

a paraplegic, a wheelchair-bound spinal victim of police gunfire, who

actually did try to hijack a plane with two grenades hidden in his

incontinence diapers. You couldn’t make it up. And if you could, it wouldn’t

be a better movie than this. The real Porfirio

plays himself, in a screen portrait of semi-paralysis startling for its

humanity, humour and (in one scene) candid sexuality. Three other Directors Fortnight films

took the eye. Rebecca Daly’s THE OTHER SIDE OF SLEEP, shot in a slow

hallucinatory style, was the haunting tale of a somnambulant Irish girl who

may or may not have committed a murder. Lots of trompe l’oeil – and trompe l’oreille as the soundtrack trades eerie sounds of

nature and the elements. Urszula Antoniak’s CODE BLUE from the Netherlands was a success de scandale

before it was even shown. Warning posters were stuck up alerting viewers

to distressing scenes. These must have been either the passages featuring

real terminal patients, in the hospital where the heroine works, or the

graphic erotic sequences, later, through which she seeks a cure for her

sexually frustrated loneliness. Oddly enthralling; a bit gauche. Best in show, Quinzaine-wise,

was Bouli Lanners’ LES GEANTS. Three young

teenagers goof off one summer, in an extended rural rampage, as if they have

decided to pay tribute to Andre Techine’s LES

ROSEAUX SAUVAGES (WILD REEDS), that classic of the contemporary adolescent

pastoral. The movie begins and ends with tracking

shots through lush riverland rushes. In between we

get a story combining Gallic growing-up with touches of Huck Finn – a

gorgeously shot sequence in a sylvan river cabin – or with surreal dabs of

Godard-worthy Dadaism. One house they break into proves a treasure-trove of

cosmetics and hair treatments. They go blonde overnight, before haring off

into the dawn at the first sound of returning owners. The tale ends

inconclusively, but in this film that’s completely apt. Will they go back to

their homes and parents? Or will they drift on deeper into their bucolic

Eden: victims of Man’s Fall re-seeking the prelapsarian

state. Back in Croisette

West the festival improved with the weather. All it took to clear the clouds

was a man-made storm, which came late in the evening of the first Saturday.

Yes: a firework display loud enough to be heard in Marseilles and bright

enough to be seen in Mar Del Plata. Blue skies arrived the next day. So did

the big-event movies, starting with Malick,

proceeding to Aki Kaurismaki, climaxing with Lars von

Trier and Pedro Almodóvar. (The Dardennes

had biked in early). The serious prizefight,

the tussle for the Palme d’Or, was thought by many to be between THE TREE OF

LIFE and MELANCHOLIA. Follies of

grandeur both – or masterpieces of reach and ambition? They gave us

respectively a history of Creation and a vision of the end of the world. THE

TREE OF LIFE presents evolution from the Big Bang to the dinosaurs in a

half-hour fairground ride, co-fashioned with 2001 effects visionary Doug

Trumbull. Quite whether this early extravaganza fits with the ensuing tale of

a family in 1950s Texas, or with the framing scenes featuring Sean Penn as

its grown-up oldest son pondering Mammon and meltdown in high-rise Houston,

is food for thought. Trier’s vision isn’t. Or rather it is:

the whole movie is a banquet for thought. ‘Melancholia’ isn’t just the

condition of Trier’s despair-prone heroine, played by a Kirsten Dunst stretched to the limit of her talent (but

successfully reaching it), it’s the name of the planet moving towards

collision with Earth. This director’s chutzpah is colossal. He made the

metaphysical uber-dramas BREAKING THE WAVES and

ANTICHRIST, rife with thoughts of life and death, good and evil, existence

and eternity. MELANCHOLIA brings a new authority and novelty of vision. It’s

a critical toss-up whether you are more stunned by the apocalypse ending –

terrestrial annihilation – or by the eerie, surreal tableaux that begin the

film. Still shots flickering with hints of motion: a lawn fiery with lightning;

footsteps quagmiring in the grass of a golf course;

a horse collapsing as if from some unseen bolt; a white-dressed bride held

back by mysterious trusses as she strides, or tries, across a moonlit lawn…. There will be, and is**, more to say

about both films. It’s a tribute to the charm and artistry of Aki Kaurismaki that, in Cannes critics

polls, his LE HAVRE kept pace with the bookies’ darlings. In this Finn’s

cinema seriousness performs a tango with comedy. Legs bent low, brows held

high, arms cinched round waists, the partners keep switching direction and

twitching heads – now this way, now that – as the music carries on. This time the music is sombre and postwar-French. The plot puts a stowaway African boy

ashore in the bleak Normandy port, where his only salvation – from fate,

cops, jail – lies with a retired author turned dockside boot-black. (Ah, the

changes of fortune for Kaurismaki heroes!) The

dapper madness goes on, amid colours whose faux-naif gravity we haven’t seen

since Fassbinder and whose shadows we haven’t seen since Marcel Carne. He’s

the main influence here. Through these swathes of chiaroscuro, varied by

studio fog, we expect Jean Gabin to step, his

craggy features shaded by a felt hat but murkily lit by a Gauloise.

Doom; foreboding; portent; done to a turn by world cinema’s greatest Sunday

painter. Pedro Almodóvar,

at the other end of Europe, is off to fresh fields and pastiches new. His

latest film is THE SKIN I LIVE IN. He’s never ‘done’ a horror film before, or not one so full of mad science and gaudy guignol. (LIVE FLESH, based on a Ruth Rendell novel, was

a medium-saignant murder thriller). Antonio Banderas, welcomed back to the Almodóvar

world where his fame began (TIE ME UP! TIE ME DOWN!), is oddly cast as the

demonic plastic surgeon who takes revenge on the boy he believes raped his

daughter. Didn’t we need a Spanish Vincent Price? An Iberian Bela Lugosi? That may be Pedro’s point. Nice Senyor Banderas, with his Mediterranean good looks and

boyish tousle of dark hair, couldn’t possibly be inflicting sex changes on

reluctant patients, could he? Doc B gives this practise the neutral name ‘transgenesis.’ The screen soon goes feral, even if the

terminology doesn’t. Early on we get the agonised young man in the mysterious

tiger suit and mask, bursting into the lab demanding emergency repair-work.

(LES YEUX SANS VISAGE meets THE ISLAND OF DR MOREAU). Later a half-naked

youngster is chained raging to a cellar wall, awaiting a cocktail of

deranging drugs. This is the Doc’s equivalent of a pre-op. The movie doesn’t get seriously surreal

till the scene of the beautiful young heroine (or is it ex-hero?) exorcising

his/her claustrophobia by writing down and across the walls of the room –

endlessly – the word ‘Respiro.’ It’s

horror-film Cartesianism: “I breathe, therefore I

am (I hope).” The Almodóvar

colours are more sober than usual. But the Almodóvar

soundtrack, its supercharged score swelling at each climax, is irresistible.

So is the story’s logic of revenge and punishment, ingenious enough to be

called Sophoclean. Perched on the edge, or almost on the

lap, of the Competition – like an orchid on a debuntante’s

knee or a dummy on a ventriloquist’s – is the sideshow ‘Un Certain Regard.’

This is where the good-but-not-good-enough (in theory) films go, having been

found of secondary merit by the Competition selectors. We all know the truth. Many films in this

section are more interesting than

those in the Competition. Braver and sometimes better. In what way is Bruno

Dumont’s HORS SATAN inferior to Radu Mihaileanu’s Palm-contending feminist tract, torrid with

tendentiousness, LA SOURCE DES FEMMES? And in what way is Mohamad

Rasoulof’s AU REVOIR from Iran a less achieved work

of cinema than Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s

ONCE UPON A TIME IN ANATOLIA, the talented Turk’s disappointing follow-up – a

longwinded police procedural – to UZAK and THREE MONKEYS. Dumont and Rasoulof

are both, in different fashions, outcasts from mainstream cinema. Though the

French mystical minimalist has twice won the Cannes Grand Jury prize, for

HUMANITY and FLANDERS, the first film was jeered at its Cannes press

screening and the second has struggled against mockers, as will HORS SATAN.

Dumont does wide, windy, untamed landscapes and people walking through them.

As they walk, they talk. Terse, runic dialogue is stolen by the wind or

sometimes merges into symbol-moments as when, here, the semi-goth girl with the black hair and nose-piercing ‘walks on

water’ to fashion a miracle for the messianic itinerant poacher she has

fallen for. The film is crazy like a fox, or like a

Delphic Sybil. It knows exactly what it does and says: complex matter about

life, love, redemption, atonement. Rasoulof is an outcast more literally.

He has been banned from filmmaking and sentenced to jail in Iran. Defiantly

he sent this feature, clandestinely made, to Cannes. It made a pair with a

documentary about fellow jail victim Jafar Panahi, co-made by Panahi, THIS

IS NOT A FILM, depicting a day in the WHITE BALLOON director’s life as he

awaited sentence. AU REVOIR is the bitterly compelling tale

of a young woman lawyer (Leyla Zareh)

seeking to flee Iran, by any means up to and including a bribery-obtained

visa for a foreign conference. She wants to escape the net. Her husband is a

jailed human rights activist. Pregnant herself, she doesn’t want her child

born and growing up in the land of the Ayatollahs. Suspenseful to the last, the film is lit

by the chiaroscuro of hope and despair and photographed in a drained colour

bordering on monochrome. That matches the anxiety, bordering on paralysis, in

the heroine. Marvellously played and directed, this is a chamber drama in

which we hear the acoustic of an entire country. Light relief? Was there any of that at

Cannes? Well, there was PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN 4, allowing visiting stars

Johnny Depp and Penelope Cruz to swing aboard the good ship Festival amid

musket-fire pops from the paparazzi bulbs. There was Nicolas Winding Refn’s DRIVE, a Danish-directed shoot-and-bash crime

thriller starring Ryan Gosling. Above all there was THE ARTIST, the sleeper

hit of the competition. French director Michel Hazanavicius

fashions a spoof silent-era comedy – black-and-white photography, intertitles – with fizzing performances from Jean Dujardin, a Douglas Fairbanks lookalike with a Sean

Connery lip curl, and the funny, talented soubrette/superbabe

Berenice Bejo. Both the last two films were among the

prizes. DRIVE’s Refn won Best Director. ARTIST’s Dujardin won Best Actor. The jury behaved with genial evenhandedness, less twelve angry men, more nine men and

women blowing kisses in every direction. Terrence Malick,

predictably, won the Golden Palm. THE TREE OF LIFE was the must-see festival

movie even before anyone had seen it. Turkey shared the runner-up Grand Jury

Prize, Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s

ONCE UPON A TIME IN ANATOLIA going ex aequo with the Dardennes’

more deserving LE GAMIN AU VELO. Israel’s Joseph Cedar won Best Screenplay

for FOOTNOTE. Best Actress went to Kirsten Dunst. She not only acts a storm in Lars von Trier’s

MELANCHOLIA. She tsk-tsk’d openly during the film’s

press conference, a Hollywood actress determined to show that mad Danish

directors talking about their sympathy with Adolf Hitler – L’affaire Trier

was the offscreen drama of the festival’s closing

days – did not get the approval of liberal movie stars sent from Obama’s New

America. Can we free westerners show our

disapproval of old-order European ubermensch politics, when the need arises? Yes, we Cannes. COURTESY T.P. MOVIE NEWS. WITH THANKS TO THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR

CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD CINEMA. ©HARLAN

KENNEDY. All rights reserved |

|

|

|

|

|

||