|

. |

|||

|

AMERICAN CINEMA PAPERS

2010

|

CANNES – 2010 THE 63rd INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL A RIVIERA RUNS THROUGH IT by Harlan Kennedy I see a French fishing village. A sky of

azure hangs above. A thousand people bustle below. The sun beams on the

boulevards; the town twinkles. And a Riviera runs through it. Even if you didn’t grow up fishing for

films at Cannes, after 20 years you feel as if you did. You feel like the

Brad Pitt of some Robert Redford-directed idyll about sparkling waters and

the nourishing, leaping, silvered memories that shaped your

growing up. “Son,” you say to anyone polite enough to

listen, “I was here when Jean Cocteau sauntered through looking for some

fly-fishing. I was here when the Hole in the Zeitgeist Gang rode in, led by Franky Truffaut and Johnny ‘Luke’ Godard, looking for

trouble and revolution. I was even here in Well, it should have been. How else do

you categorise the 63rd Cannes Film Festival, weird and wondrous,

where every competition pic seemed made against the current? Only the

currents differed, and the directors’ reasons for swimming against them. We

started on gala opening night with ROBIN HOOD, Ridley Scott’s revisionist

romp about the man in tights, attempting to prove that Robin Hood (actually

Robin Longstride) didn’t wear any tights – he

didn’t even wear green or live in a wood – and that Maid Marian (actually

Lady Marian) was a married woman. Follow that? Cannes did with Bertrand

Tavernier’s THE PRINCESS OF MONTPENSIER, a counter-current costumer,

crackling with passion, from the French craftsman of quiet contempo dramas (A WEEK’S VACATION). Then came Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s

BIUTIFUL, swimming against the flow of his previous multi-plot output (BABEL

and Co) with the intimately focused portrait of a dying street gypsy (Javier Bardem). Then – best and most defiant of all – there was

Mike Leigh’s ANOTHER YEAR, a cine-salmon so strong it out-muscled all

contenders in making for the head of the river. This is the finest film yet from the

British helmer, previously Golden Palmed for

SECRETS AND LIES. Leigh’s way of reversing the practice of a lifetime – and

our expectations – is to multiply his plots and characters. No Leigh critic

can say of ANOTHER YEAR, as of some past movies (including his last,

HAPPY-GO-LUCKY), “Oh he takes a little bunch of interlinked neurotics and mannerises them to death.” Here the main characters, plainly yet

compellingly played by Jim Broadbent and Ruth Sheen, are not mannered at all.

They’re a greenish couple sustaining themselves in exurban London (with

allotment garden for homegrown vegetables) whose

weirdest tic is to hold open house for friends and family. These do include a

few recognizable Leigh oddballs: the middle-aged, overweight loner (Peter

Wight), hooked on oral solaces (eating, drinking, chain-smoking), who vainly

pursues the aging, chattering, insecure party girl (Leigh veteran Lesley

Manville), who in turn has an unrequited yen for the host couple’s son, a sly

extrovert with his own amatory secrets (Oliver Maltman). Just when we think we’ll be staying with

this lot till the film’s end crawl, the filmmaker ups sticks and moves to a

northern-England funeral. A widowered relative

(David Bradley) takes centre screen. His violent, disaffected son blows a

brief hole in the protocol of mood-and-plot unity. The film’s rhythm becomes

at once brilliantly uneasy and menacingly becalmed. Then, just like the

seasons that cyclically chapter-head the story’s

sections (‘Spring’, ‘Summer’ and so on) we wind back to beginnings, after the

long year’s journey into bleak and comical enlightenment. The movie is utterly beguiling. Chekhov

in Limeyland. Its mastery lies in the connection

made between different styles of characterisation. Manville’s social

butterfly, with her semi-broken wings and toujours gai nerve reflexes, is a type known

from past Leigh dramas, starting with Alison Steadman in ABIGAIL’S PARTY. But

actress and director here add extra innerness, extra nuancing, sometimes in a

mere wordless glance. By the time the most touching scene arrives – a

meeting-quaint between Manville and Bradley, home-alone as a house guest down

south while his hosts Broadbent and Sheen are out – it becomes a triumphant

entente between opposites. Not just between the manic would-be cosmopolite

and the dour lump of northern rock-salt; but between the tics-and-tropes

style of portraiture, suddenly made human, and the minimal realist style,

given (by Leigh and actor Bradley) just that extra wit, forwardness and

vividness. From the other side of the world, in the

Year of the Salmon, came the competition’s two other big fish. A brace of

eerily memorable Asian movies, their images as fluid and their spell as

fugitive as their alluvial settings. A river runs through one film; a

waterfall and magical pool are at the heart of the other. Lee Changdong’s

POETRY from South Korea gave a whale of a part – never mind smaller aquatic lifeforms – to Yun Junghee,

playing a granny bringing up a teenage brat suspected of gang-rape

activities. He’s only a schoolkid, but a girl has

killed herself: we see her float downstream in scene one. Grandma is a

touching biddy, still holding out for refinement (pastel-print jackets,

lace-style white scarves) as Alzheimer’s Disease moves in and amour-propre

starts to move out. The palsied old man she works for, as maid and carer, wants

more for his money at bathtime than just a back

rub. The old girl goes to poetry classes:

she’ll transcend her life if it kills her. But what to do about

grandson? Director Changdong,

who made the superb SECRET SUNSHINE, a Cannes hit two years ago, again zones

in on bereavement, vulnerability, age and the ambivalent motives of those who

‘care’. In the earlier film it was a creepy religious sect. Here the fathers

of the gang-rape boys band together, and recruit Grandma, to appease and buy

off the dead girl’s parent. Will Gran blow the whistle? Will Gran even shop

her own brat to the cops? The bewitching delta of story trajectories – even

though we know they will all end and merge, beyond the film’s own completion,

in the sea of death – are magically conjoined in the source character. Old

age is no respecter of the quest for tranquillity; at least while life lasts

and the heart, mind and soul are open to fresh truths and challenges. From Thailand comes Apichatpong

Weerasethakul’s UNCLE BONMEE RECALLS HIS PAST

LIVES. This poet of the Asian screen made the haunting, fantastical TROPICAL

MALADY, another Cannes revelation in its year, and now re-summons that

movie’s jungle imagery and ghostly supporting cast. The ‘Uncle’, tended by

his small family, is dying of kidney disease – his belly in bedroom scenes a

spaghetti junction of tubes siphoning off effluvia – while his mind is

swirled about, no less convolutedly, by spirits and essences that become more

visible, more tangible as the tale progresses. A dead sister materialises at the meal

table. A son who mated with a ghost monkey returns as, yes, a ghost monkey.

(Loved the two red eyes burning out of the dark Chewbacca fur). Soon we watch

as the main characters, dead and alive, troop into deeper caverns of storytelling,

journeying Jules Verne-like to the centre of their spiritual or karmic

selves. Jungles, caverns; a waterfall at whose foot – a fairytale

within fairytale – a princess is ravished by a

catfish. By the last scene, in which

two key characters or their avatars part from their bodies to go off

for a Thai restaurant dinner (sic) while their source selves stay home to

watch TV....Well, by that time you are either in seventh heaven or in the

seventh circle of Incomprehension Hell. Weerasethakul freely admits it helps to

have been born a Buddhist. In Thailand transmigration of souls – people

turning into animals – is part of the normal traffic of thought, even if not

of belief. But what sentient westerner

can resist the spooky spell and eerie flow of this film’s phantasmagoria?

What clinches UNCLE BONMEE as poetry – screen poetry – is its very

matter-of-factness. The beauties are entranced and entrancing, yet they are

spoken not sung. They issue from the same daily life, the same marketplace of

the mundane, as the family meal, the evening at home, the visit to the

restaurant, the tragic but universal domestic rites

of the terminal disease… It is easy to believe in transmigration

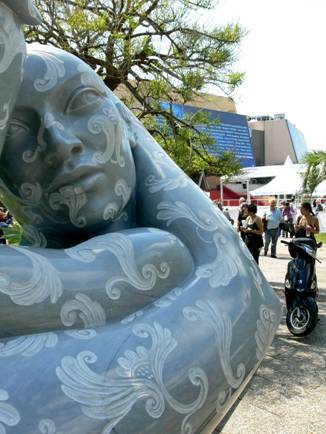

and metamorphosis at Cannes. Step out of your darkened cinema, and the Croisette – the palm-sentinelled beachfront boulevard –

is a 24:7 wonderland, even in years when Tim ALICE

IN WONDERLAND Burton is not president of the jury. A man dressed as an 18th

century dandy dandles two dancing cats on his shoulders. A

troupe of breakdancers perform their

upside-down gyrings and gimblings.

The town’s sand-sculptor finishes his latest Neptune or recumbent mermaid.

(This year he gave us Batman too). A gaggle of zombies, in a promo stunt for

the latest living-dead romp, stagger towards you, one carrying his head under

his arm. And just occasionally there’s a plain and simple celebrity. Ooh

look, there’s Oliver Stone (squiring WALL STREET 2) or Cate Blanchett, looking fresh for the fight as France gets its

first glimpse of ROBIN DU BOIS. Ah Cannes. If you didn’t exist, the world

would have to invent you. But didn’t the world invent you anyway? All your

accretions and accessories, at least, of culture and razzmatazz, of picture

premieres and partying. The last two are usually reserved for the dark hours,

not that Cannes is ever really dark. Lit by the jewelled wattage of the

Mediterranean sky – even the seagulls are luminous at night – the town

answers the stars with its own billion points of light. The The host nation does its best to mortify

us. And itself. Two competition films addressed the agonized history that is

north-west Africa. To former colonists this is still, it seems, an unhealed

abscess. Xavier Beauvois’s OF GODS AND MEN

powerfully imagines the human drama underlying a true story: the deaths of a

group of monks in Algeria, 15 years ago, when Islamic terrorists raided their

monastery and led them off to presumed slaughter. A sober, even sombre, mise-en-scene paints their devotional lives in shades of

grey while allowing the actors’ humanity – Lambert Wilson as Father Superior,

Michael Lonsdale as the elderly friar running the missionary clinic – to

touch in life-giving flesh tones. The ending is shocking, though even here

the film sustains a reverential distance, reverencing not God but those who

bravely, even when blindly, serve him. As they hymn their defiance, who is

not reminded of the tolling close of Poulenc’s opera DIALOGUES OF THE

CARMELITES, the prayerful music of the martyrs rising against the grisly

punctuation of their deaths? Flashier and more of an intended

flashpoint was Rachid Bouchareb’s

HORS LA LOI (OUTSIDE THE LAW). Debate raged in the French press before the

screening. The screening itself was a high-security

gig worthier of an airport: bags searched, bottles impounded, bodies frisked.

No bomb went off, unless you count the movie itself. Bouchareb,

whose last celluloid explosion was INDIGENES (DAYS OF GLORY), about the

ill-treatment of foreign-born French soldiers in World War Two, tells the

history of the FLN, the Algerian resistance movement. The lives of three

brothers (played by the earlier film’s stars Jamel Debbouze, Roschdy Zem, Samy Bouajila)

split apart, then come together, as the flames of anti-colonialism rage. The

fictive story is a little corny, big with contrivance and tragic irony as it

strides across the years. (Mix in your imagination Pontecorvo’s

BATTLE OF ALGIERS and Victor Hugo’s LES MISERABLES). But the cold water of

reality – murder, torture, betrayal – is thrown in our faces often enough to

keep us alert and wired and discomforted. France also chipped in with THE PRINCESS

OF MONTPENSIER and TOURNEE (ON TOUR). The first is a vivid costumer from

Bertrand Tavernier, a director we had feared lost after his last film, the

US-made IN THE ELECTRIC MIST, a slab of loony southern gothic starring Tommy

Lee Jones. PRINCESS is set in 17th century France and based a

novel by Madame de La Fayette. It skitters stylishly through war, love, royal

politics and fine-turned dialogue. Definitely one for world arthouse distribution. TOURNEE, for contrast, is the tale

of a burlesque troupe managed by Mathieu Amalric

(also the film’s director), who does tousled sleaze to a T and an S. This

charismatic scuzzball could be Archie Rice from THE

ENTERTAINER crossed with Charles Aznavour in SHOOT

THE PIANIST. Minor, but fun. And lots of gratuitous nudity. French too, at least in language, was Mahamet Saleh-Haroun’s UN HOMME

QUI CRIE (A SCREAMING MAN) from Chad. The ABOUNA director deploys a dark,

poignant palette in portraying his strife-torn country. Here is the tale of a

tragic father, guilt-racked after sending his son (and work colleague) into

the army, partly to preserve his own job as a pool attendant in a tourist

hotel making economies. Horrors start to happen. Grief rains down the screen,

slow and ineluctable, like dirty rain. The ending – a bleak rhyme with the

happier opening scene of father and son enjoying a breath-holding contest in

the out-of-hours pool – is simple, laconic, devastating. There was not much you could call

‘escapism’ at the 63rd Cannes Film Festival. Takeshi Kitano took

time off from his serious self to make OUTRAGE, a Yakuza thriller. But the

violence is so extreme – finger-loppings, a

gruesomely novel decapitation – that two hours in Japanese gangland are

hardly recreational. FAIR GAME was Hollywood’s bid to lighten the tone. But

even with Naomi Watts and Sean Penn adding lustre, the true tale of outed CIA agent Valerie Plame and her persecuted husband

Joe Wilson – who made the mistake of providing Bush and Co with WMD-doubting intelligence

before the Iraq invasion – is a shock to the system, assuming your system

doesn’t know the story already. Plame and Wilson suffered badly at the time.

But both were in Cannes, smiling for the paparazzi. So for now at least, they

live ‘happily ever after’. And Bush is back in Texas. The film you approached with least

expectation of escapism was Cristi Piuiu’s AURORA. Puiu made the

grimly brilliant DEATH OF MR LAZARESCU. Here he was, at it again, we hoped,

with a 3-hour film about a divorced man (played by the director), plagued by

society and himself, who takes to murder. Yummy: there would be lots of

Romanian schadenfreude,

bitter comedy, social satire. And it’s only two

years since Romania won the Golden Palm (Cristi Mungiu’s FOUR MONTHS, THREE WEEKS, TWO DAYS). Sorry, we’re all out of schadenfreude. And the rest of the shopping list.

AURORA limps at a slow pace, going nowhere while accumulating a great deal of

useless detail. You can learn how to re-plaster a house. In some scenes you

can almost literally watch paint dry. What a letdown.

Still, Puiu is making four more films in this

series. Keep hope alive. AURORA showed noncompetitively in Un

Certain Regard, the main sideshow at Cannes. This year’s programme was topped

and tailed by Portugal and South Korea. The last film shown, Korea’s HAHAHA,

also won the event’s top gong, the Prix Un Certain Regard. (For ‘noncompetitive’ read ‘oh all right, a bit competitive’).

This award was Greek to me, never mind Korean: Hang Sangsoo’s

film is a fey, logorrheic romcom hard to sit

through for two reels, never mind two hours. But the Portuguese opener. Ah Manoel. Ah Dolly. Yes, it’s the Manoel

De Oliveira show again. Now 101, the prolix Iberian remains spry enough to

take a Cannes bow, never mind to make a feature, THE STRANGE CASE OF

ANGELICA. This is like some divine coition between Hitchcock and Borges. A

young photographer (Dolly regular Ricardo Trepa)

falls in love with the face of a dead girl he is asked to lens-immortalise in

her coffin. She ‘comes alive’ in her photographs. The photographer’s halo of

otherworldly joy starts to disturb his boarding-house colleagues, a typical

bunch of De Oliveira gossips and meal-table philosophers. Then there is his

weird compulsion to watch, photograph and tape-record the singing diggers on

the vine terraces of the opposite hill….. It’s a film about past, present, future;

about nostalgia for what was and ‘nostalgia’ for what cannot be; about speech

and song as differently terraced states of being; about the dimension between

sentient life and prescient life-before-death, which an artist of 101 is

qualified, like no other, to know and address. We say ‘like no other’. But in

a year’s time De Oliveira will be 102: better qualified still. And ready, no

doubt, with his next billet-doux from the near-beyond. So to the prizes. The spotlights waved,

the fanfares sounded. The fireworks worked. The women in designer dresses and

the men in penguin suits climbed the red carpet. The subsidiary prizes, read

out by jury prez Tim Burton (wearing geek chic

specs and hair coiffed in the dragged-through-a-hedge-backwards style) and

his crew, were as follows in ascending order. Jury Prize to Chad’s THE SCREAMING MAN.

Best Screenplay to Korea’s Lee Changdong for

POETRY. Best Director to Mathieu Amalric. (Bit of a

surprise, but it’s a Gallic fest). Best Actor shared by Spain’s Javier Bardem (BIUTIFUL) and Italy’s Elio

Germano (LA NOSTRA VITA). Best Actress to Juliette Binoche (for her incandescent performance in Kiarostami’s CERTIFIED COPY). Grand Jury Prize to Xavier Beauvois’s OF GODS AND MEN. Finally the Golden Palm. Bent by winds of

acclaim, combed by breezes of beatification, the palm bowed with generous

reach towards Thailand. Yes. It was Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s UNCLE BOONMEE WHO RECALLS HIS PAST LIVES.

Mr A-Pong thanked the gods and spirits of his native land. We thanked the

gods and spirits of Cannes – those topless deities that hover over the Croisette with tans and Dior sunglasses – for the

privilege of having seen the film and witnessed its apotheosis. Yes, miracles can happen. A final one

occurred on my plane home. The Catholic priest-critic colleague who once

accosted this writer, when peering penniless-seeming and roughly dressed into

a Cannes shop window, and promised him alms, finally – after many years –

handed them over. As the Euro cent changed hands (roughly the value of one US

cent), the angels in heaven cheered and applauded. And I was at peace. It wasn’t a Palme d’Or, but it was an Alm de Cuivre (copper). This

priest friend is now saved. He is able, when he departs the Vatican on his

final pilgrimage, to tell St Peter: “I gave him the moolah.”

St Peter, the patron saint of bouncers and doormen, can say: “In you go,

then. And the drinks are free after the first one.” COURTESY T.P. MOVIE NEWS. WITH THANKS TO THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR

CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD CINEMA. ©HARLAN

KENNEDY. All rights reserved |

|

|

|

|

|

||