|

. |

|||

|

AMERICAN CINEMA PAPERS

2012

|

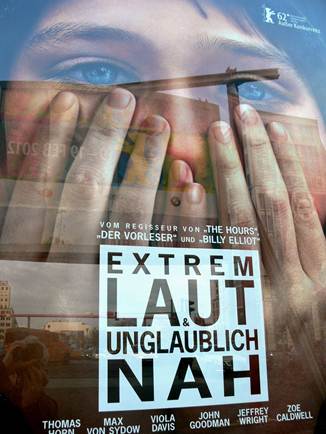

BERLIN FILM FESTIVAL – 2012 THE FAMILY OF MAN by Harlan Kennedy

All hail the new Germany. Clean, upright,

forward-looking: an example to us all. Already in troubled times it is taking

new shape as a Motherland – let’s stay away from the other word – to Europe.

The family of EU nations looks to it for succour, guidance, reassurance. And

of course money. What else are parents for? What a topic: families. The family of man

– and woman and child – was under the scanner as never before at the 2012

Berlin Filmfestspiele. You recognize an emergent

anxiety, planetary or hemispheric, from its reflection, vivid and premonitory,

in art and cinema. Are we afraid, not just in Europe, of becoming orphans? Of

being chucked out in the snow? Of losing guidance, love, beneficent

authority…? It was the theme of the most high-profile Hollywood film at

Berlin: Stephen Daldry’s EXTREMELY LOUD AND

INCREDIBLY CLOSE (German title, EXTREM LAUT UND UNGLAUBLICH NAH). Boy looks

for missing dad in the stunned aftermath of 9/11….

Perhaps the topic of ‘nuclear families’

is part of a post-nuclear age. Split the notionally indivisible atom of

familial togetherness and look at the mayhem and fallout. Alternatively, look at three of this

year’s Berlin Film Festival competition films, one each from America, Hungary

and, yes, Germany. Between them they box the compass of an increasingly

resonant, and metaphorically expanding, western theme. “Jayne Mansfield’s Car”:If You’ve Got It,

Haunt It Hollywood – perhaps naturally – came up with the

most traditional family show. Billy Bob Thornton’s JAYNE MANSFIELD’S CAR has

Robert Duvall, Kevin Bacon, Robert Patrick and Thornton himself, playing a

southern baroque dynasty catalysed into crisis and multiple self-revelation

by a death. Usually these films – all-star ensemblers

with en-suite tragicomic catharsis – have the word ‘Heart’ in the title:

PLACES OF THE HEART, CRIMES OF THE HEART. Heavy hearts, wounded hearts,

yearning hearts….hearts of the south. The family that stays together frays

together. That’s another message. America is big on blood solidarity, but

some of that blood will get on the walls. In Thornton’s film, set in Alabama

in 1969, grandma has died, Duvall’s ex-wife. Not

only the sons foregather (no daughters, this is Macho County) but also the

grandchildren and the deceased’s new family, the one she married into.

They’re English, which brings over John Hurt and daughter-in-law Frances

O’Connor, a floozy with a cut-glass voice who seduces the

ever-so-slightly-doolally Thornton. All the sons, it happens (this again is

the south), are a mite doolally. They all served in World War 2. Bacon, an

aging hippy, protests the Vietnam War. Patrick is a right-winger to shame

Barry Goldwater. Thornton shows off his cherished collection of three

“airplanes” – actually, vintage cars – to O’Connor, who responds by acceding

to his request that she go buck naked and recite ‘The Charge of the Light

Brigade.’ Thornton, at a watching distance, does what a man’s gotta do. The week wears on, sometimes funny,

sometimes endearingly macabre. In the key scene, the title scene, Duvall and

Hurt (a double act so droll and well-played it has sitcom potential) visit a

touring exhibit of Jayne Mansfield’s car, the one she died in in her grisly

accident. And which she still haunts, to judge by the penny-dreadful fake

decapitated head positioned, for spectator-ghouls, on the front seat. The

scene is there to say that even the most perfectly tooled unit – car or film

star or prosperous family – is only a setback or accident away from tragedy.

It also says, of movies like this: they’re old-fashioned, beguiling and

haunted by heritage, but they can’t, in all honesty, have much more mileage

left on the clock. “Just the Wind”: Hungary for Life Hungary’s JUST THE WIND, which won the

runner-up Special Jury Prize, is a newer, more radical family movie. From the

start it subjects the family unit to a startling, disorienting diaspora. For

half an hour we hardly know that these characters, whose stories are

intercut, are a family: Romanies in a small village lost in a remote countryside.

The young tyke skips school to go on petty-thieving forays. The dim-witted

girl rests her head on her schooldesk during the

woman teacher’s earnest yap about the evolution and primacy of the human

brain. (“Curiosity,” she says, “distinguishes us from the animals,” though it

doesn’t seem much to distinguish this girl). A middle-aged woman holds off

the threats of a mafioso loan shark, who sits

stroking a watermelon on his lap like a cat. There’s also a scruffy old man,

presumably grandpa. And an absentee husband, preparing a hopeful nest for his

clan in Canada. Yes. They’re gypsies. And there has just

been – the pre-title tells us, shading truth-based incident into coming

fiction – the brutal reported murder of a gypsy family. “Hate crime.” Even

the cops here hate the Romanies, though one cop

bestows a half-hearted exemption on the pre-slain family as he and his buddy

clean up the mess: “They were hardworking gypsies. No point in shooting

them.” The gypsy family, put plainly, is not

welcome in the larger social family. Accordingly this one operates – to the

movie’s gain in freshness of structure and enigmatic spell – outside family

rules. They seldom get together; barely interact; yet run, in their way,

invisible rings around their provincial community. The boy is a guerrilla

lawbreaker with his own forest dugout (an Ali Baba cave) for stolen goods.

The mother cleans for a bullying property type, another mini-mafioso, but has the wit to repudiate his insults and

cling on to her job. The daughter, though dim, is given an extraordinary

scene plaiting flower garlands with a pal, in a meadow, as if to say that

human grace and self-transcendence are not all about paying attention in the classroom. The dispersing of these characters in

early scenes pays rich dividend at the end. When they come together for the

gruelling denouement, it’s as if not just three characters have converged (or

four with lesser-seen grandpa) but three worlds, three sovereign, fully

realised lives. Three fates rich to be measured, and, depending on the reach

of our empathy, mourned.

“Mercy”: Polar Bear Goes for Gold Germany, in collaboration with Norway,

gave us Matthias Glasner’s

haunting GNADE (MERCY): all about a family at the edge of the world.

Hammerfest, a Norwegian town on the edge of the Arctic, is the spectacular

home-in-exile of this German ménage

of three – hospice nurse Maria (Birgit Minichmayr),

gas-plant engineer Niels (Jurgen

Vogel) and camcorder-wielding son Markus (Henry Stange)

– whose intimacy is shattered by a road accident. Maria, driving one night in

the icy dark, runs into what might be an animal or might be a human. She

looks back briefly; sees nothing; drives on and says nothing. Or is it that the family’s lack of true intimacy, the lies it

lives on, including Niels’s affair with a

co-worker, are exposed by this sudden larger lie. A girl is found dead by the

roadside next day. Maria, confiding only in her husband, clams up about the

collision. The family that covers up together corrupts together. In scenes aptly icy in look and feel – Glasner is a master of the tableau barely vivant –

everyone does what he or she thinks best for their nearest and dearest. The only

external perspective comes from son Markus, whose mania for home-movie making

smacks of mischief or of an Ibsenite

avidity for truth: that avidity that destroyed the family in THE WILD DUCK

(while notionally saving the world for honesty and candour). It’s even more Ibsenite – the Norwegian connection! – that

the tale’s dubious messiah is a youngster, as destructively renewing as Hilda

Wangel in THE MASTER BUILDER. When Niels and

Maria finally collect enough courage to tell the dead girl’s parents of their,

or Maria’s, role, it is too late. For the couple who have lost their child, a

healing scab is uselessly picked open. For the couple we have come to know,

the emotional wounds and scarrings are already

there, mapped and irrevocable. Maybe they should never have made the effort.

Or maybe it should never have become

an effort. It should have been the first instinct, the rapid response,

unsullied and un-delayed by the false faith of loyalty to loved ones, who are

merely, in so many cases, an alibi for oneself. Families: Can’t live with ‘em,

can’t live without ‘em. Perhaps, this troika of Berlin movies

tells us, we should all stop living by the rules of the immediate family and

stretch our vision, and our power to engage and identify, to the rest of the

world. At worst this might produce a “family”

that experiences the traumatic crumbling of moral preconceptions and

ideological divides, like the bonding of terrorists and hostages in Brillante Mendoza’s Berlin-lauded kidnapping drama

CAPTIVE from the Philippines (a bonding explicitly compared, through the

film, to an enlarged family). At best it might mean – and to judge by

world reaction to present-day horrors in Syria or former horrors in Bosnia it

already means – that we start caring about not just other members of our kith

and kin but other members, however far flung, of that family we call Planet

Earth. COURTESY T.P. MOVIE NEWS. WITH THANKS TO THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR

CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD CINEMA. ©HARLAN

KENNEDY. All rights reserved |

|

|

|

|

|

||