|

AMERICAN

CINEMA PAPERS

2008

|

BERLIN FILM FESTIVAL – 2008 BEAR-FACED CHIC by Harlan Kennedy All the world loves a bear. The cuddly ursine has held sway so long at

the Berlin Film Festival that it defines everything about this event.

Adorable, savage; lumbering, graceful; vulnerable, feral. It is a home to God

knows how many grateful parasites. (Some impudent people include us critics

in that category). And – forever in its favour – it will kill to protect

those it loves and defend what it believes to be its territory. And what is that territory? What is the Berlinale’s

beat and bailiwick? It’s a macrocosmic interest in human history, combined

with a microcosmic fascination with the margins of human behaviour. So we

expect, each February, movies about world upheaval and gay lifestyles, about

Nazism and transvestism, about the war in Iraq/Afghanistan and the war –

eternally modern – for individual life, liberty and happiness. Sometimes these things come together and show us the human face of

history. If there were two better films in Berlin than Benjamin Gilmour’s SON

OF A LION, made in Pakistan by an Australian, and Ameer

Sulthan’s PARUTHIVEERAN, made in India by an

Indian, no one screened them for me. Shown outside the competition in a

better-than-ever Forum event, they are walloping reaffirmations of subcontinental cinema. And if you think the fact of

Aussie direction makes the first movie as much Antipodean

as Asian, you reckon without the teamwork of Gilmour’s all-Pashtun nonprofessional

collaborators – actors, craftsfolk, assistants –

who helped him tear up his written script and extemporise his story. Gilmour,

a former unit medic in the movie industry, first went to Pakistan as a

tourist, then returned to make his directing debut, convinced there were

burning stories to be told that never could be told, with proper

passion, outside the place itself. War versus peace. Ignorance versus learning. Hatred versus

understanding. These are SON OF A LION’s themes and

none are more important on the planet. But importance – or self-importance

– has no place in this beautiful, unadorned tale of an 11-year-old boy

tussling with his ex-mujahideen dad in a village that makes guns and wants

its sons to go forth and use them. Darra in the

Northwest Frontier tribal territories really is a village-sized arms factory.

Tourists go there to fire off rounds and have their pictures taken as

let’s-pretend jihadists. The boy wants to go to school, like most of his chums. His dad, an old

warrior who helped chase the Russians from Afghanistan, wants him only to be

a shooting-and-fighting machine, primed to join the next tide of martyrs for

Allah. Around this father-son bearfight whir, like

everyday exotics in the zodiac of life, the friends, uncles, villagers,

grandparents who each have a pitch to make. An uncle in semi-distant

Peshawar, to which the boy rides an occasional bus for tooth-repair

appointments (cueing the funniest dentist scene in modern cinema),

high-handedly enrols the youngster in a city school. The lad’s dad

practically ups and slaughters him. Meanwhile a choric collection of village veterans shoot the breeze and

chew the hash, musing on war, peace and things between. One man remembers the

last film he saw in a cinema: “The mujahideen were the heroes. It was called

RAMBO 3”. Another affirms local opinion on the causes of 9/11: “Everyone

knows the Americans did it themselves.” No wonder we root for the boy’s schooling. Knowledge might win out

over folklore; guns might be turned into computers, the way swords used to be

turned into ploughshares. But the film’s strength is that everyone seems

human here, even the implacable father, for whom every dawn marks a new day

to fight the infidel. According to director Gilmour the actor playing him, Baktiyar Ahmed Afridi, was a

firebrand warrior once himself: he helped chase the Russians from

Afghanistan. But he had the judgement and discrimination, more recently, to

refuse to fight for the restoration of the Taliban. The feuds that blind us have their human face. There are ways of

‘seeing’ – with help from art and cinema – even through the smoke of battle

and the pall of prejudice. Ameer Sulthan’s PARUTHIVEERAN is a timeless story rather than

historical one. Set in a non-denominational ‘now’, somewhere in rural Tamil Nadu, its tale of caste prejudice and the bloody issue of

conflict between families is as old as Indian time. Black-and-white

flashbacks depict the moment when the heroine-as-child saved the

hero-as-child’s life. As young grownups, she loves him, he – for two hours of

the movie a promiscuous wanton – finally woos her. But their families throw

jagged impediments between them, from ancient feuds to the inviolable rules

of caste. A climax of grief and horror comes, with Euripidean

force, at the end of a movie that has juggled comedy, drama, song and dance

with Bollywoodish flair. Yes, history has a human face. The older the history, the more

wonderstruck we are by that humanity – and yet the more reassured, as if by a

memory we had forgotten we always had. It isn’t just films that do it. In Berlin, even a 200-year-old great

composer and 3,000-year-old Egyptian queen can show us their human faces. On

my first day in town, I went to a concert in an outlying folk-stadium. Mr and

Mrs Working Class and their kids swarmed by the hundreds or thousands into

this hangar on the banks of the River Spree. Honorary Hun Sir Simon Rattle

conducted a Berlin Philharmonic which he has moulded into a classical

orchestra that can double as an up-market pops band. They spanked out

Beethoven’s 2nd and 3rd symphonies like divine rock and

roll, titanic and exuberant. They had to spank it out to drown the

mewling of babies, some of whom crawled up and down the aisles, while older

tots ran about or jumped in and out of parents’ laps. The rest of us just

drank in the music (some just drank…). It was made human, made intoxicating,

made approachable in its glory by the setting and the Sunday-treat family

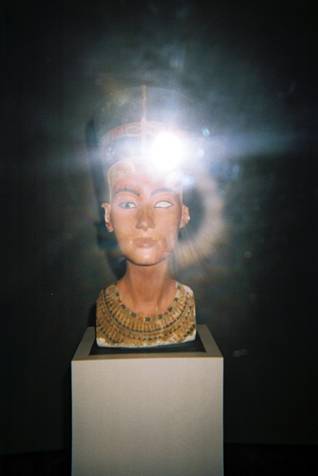

turnout. On my last day in Berlin, I wandered into the city’s world-famous

Egyptian Museum. Here is the legendary

bust of Queen Nefertiti. The museum’s portable audio

commentary says, by way of prologue, “We know you’re only here to see Nefertiti”. The royal consort’s head, neck and shoulders

stare out from a pedestalled glass case. She is in

startling Technicolor – the only colour, virtually, in the whole museum – and

she looks like Anouk Aimee made up for a Nile-side

movie epic. At the same time she seems a living, musing mortal, a gazer-out at

life’s richness who is as bemused and wonderstruck as the rest of us. With

her one completed eye and one incomplete, she could, in her exalted

complicity, be winking at us. (She’s probably reacting to flashbulb-popping

tourists like me, who then get taken to task by the museum’s guards). She seems so informal because she never, before the last century, went

on display. This bust was found, perfectly preserved, amid the rubble of a

sculptor’s workshop. Art should be so lucky. What could be more virginal than

a gazing face that was never gazed at? Perhaps that is the magic of Berlin’s film festival. The European

year’s first big movie spree really does offer the thrill of discovery. Even when it looks back on history, it also

forward-gazes with fresh, expectant eyes. Even when a movie says of its story

or setting, “This is the past”, it also gifts itself as a piece of the present,

offered to us, the audience, as keepers and stewards of the future. I’ll have to spend more time in this town….. COURTESY T.P. MOVIE NEWS. WITH THANKS TO THE

AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD CINEMA. ©HARLAN

KENNEDY. All rights reserved |

|